Eugène Carrière: He faced his imprisonment with a courage that was serene

Carrière enlists in the Franco-Prussian war, he gets imprisoned, he gets out, he recovers a bit, and heads back to Paris — gotta get back to the dream of being a painter.

NOTE* French text first, English follows. I hope this is easy to follow. Please let me know if it isn’t. We’re going into 1870-1871 timeframe now.

—Sur ces entrefaites,

la guerre éclata. Après les premières défaites, il partait pour Strasbourg, il voulait rejoindre ses parents, prendre sa part des épreuves communes. Strasbourg déjà était investee par les Prussiens ;il s’engagea pour la durée de la guerre et rallia la garnison de Neuf-Brisach. La place écrasée d’obus, bientôt capitulait et il était interné en Saxe, dans la ville de Dresde. Aux souffrances de la captivité, il opposa son courage tranquille d’homme qui n’aime pas les gestes inutiles, il se ramassa et subit ce qu’il fallait subir. Un soir, chez Alphonse Daudet, il évoquait ces souvenirs lointains : pour toute nourriture dans les premiers temps, la soupe au millet ; les camarades et lui en blouse bleue, en sabots, « tout semblables aux facteurs ruraux l’été, — et cela pendant qu’il gelait à pierre fendre », et il concluait qu’au fond les prisonniers n’avaient pas eu à se plaindre des Allemands.

—Alors, on a été très aimable avec vous, lui dit ironiquement une dame qui attendait sans doute des plaintes de cet homme qui ne se plaint pas.

—Oh! madame, on n’est pas aimable avec vingtcinq mille hommes. (Journal de Goncourt.)

—In the meantime,

the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870. After the first losses, he left for Strasbourg, he wanted to be with his parents, to do his part in these collective trials. Strasbourg had already been invaded by the Prussians; he enlisted in the war and rallied the garrison at Neuf-Brisach. The place crushed by shells soon surrendered, and he was interned in Saxony, in the city of Dresden. To the insufferable weight of imprisonment, he faced it with a courage that was serene*, that’s from a man who doesn’t like pointless demonstrations. He pulled himself together and endured what had to be endured. One night, at Alphonse Daudet’s house[1], he recalled these distant memories: millet flour soup, the only food they had in the beginning; he and his fellow soldiers in blue blouses and clogs, “just like the country postmen in the summers — and that was when it was freezing cold,” (bone cold) and he concluded that deep down the prisoners hadn’t had the instinct to complain about the Germans.

—”So, we were very friendly to you,” she said to someone, ironically, a woman who expected without a doubt that this man would complain but he did not.

—”Oh! Madam, one isn’t friendly to 25,000 men.” (Journal de Goncourt.)

[1] Daudet was a French writer known for his short stories about provincial life in the South of France. Carrière had a pretty distinguished entourage.

—Carrière trouvait là-bas,

paraît-il, le temps de travailler : j’ai pu voir un dessin, assez banal d’ailleurs, une composition centrale entre deux épisodes de la guerre de Vendée[1], qui porte cette suscription; Frontispice d’un futur ouvrage d’un futur écrivain qui partage ma captivité, décembre 1870.**** Un hasard lui permit de visiter l’admirable musée de Dresde, mais trop vite : de tant de chefs-d’oeuvre, dont les Rembrandt que l’on sait, il n’emportait qu’une image, celle de la madone de Saint-Sixte, que le génie de Raphaël, par le balancement de deux lignes, enlève d’un si noble élan. La guerre avait reculé bien des choses dans le passé. Les longs mois de captivité écoulés. Carrière regagnait Strasbourg, y recevait bon accueil et, après avoir pris quelque repos auprès des siens, revenait à Paris mener la dure vie qu’il avait choisie. Élève de l’École des Reaux-Arts, il appartenait à l’atelier de Cabanel, qui semble avoir eu le rare mérite d’aimer l’originalité chez les autres et de ne pas porter atteinte à celle de ses élèves.

—Carriere found,

somehow, the time to work over there: I got to see a drawing, rather bad, actually, a composition centered around two scenes from the War de Vendée (French Revolution) that carried this title on top, “The cover of a future book by a future writer in captivity with me, like me December 1870.” By chance, he got to visit the impressive Museum in Dresden (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden), but not for long: out of all the masterpieces, including the Rembrandts that we all know, he only captured one image, the Sistine Madonna that the genius of Raphael, in the swing of two lines, lifts with such a noble momentum. The war had really turned the clock back in time in many respects. The long months spent in captivity dragged. Carriere went back to Strasbourg, where he received a warm welcome and, after recovering a bit close to his loved ones, came back to Paris to the hard life that he had chosen to lead. As a student at l’École des Reaux-Arts, he belonged to the studio of Cabanel, who seemed to have had a rare quality of liking originality in others and didn’t discredit it in his students.

****Footnote: Les vieux papiers ont leur destin. On vendait l’atelier d’un pauvre garçon, mort à la peine. Un encadreur, parmi ses acquisitions faites un peu au hasard, découvrit tout un lot de projets, de dessins, qui portaient le nom d’Eugène Carrière ;il le donna k M. Pontremoli, pour lequel il avait encadré des toiles signées de ce nom. J’ai trouvé là des documents précieux, non seulement sur les besognes que Carrière accepta pour vivre, mais sur la souplesse de talent, sur la variété d’aptitudes qui le rendirent propre à les remplir.

****Footnote: Old papers have their destiny. The studio of a poor boy, who suffered a painful death, was being sold. A framer, among the acquisitions made a bit haphazardly, discovered a lot of projects, of drawings, that bore the name Eugène Carrière; he gave it to k M Pontremoli who framed the canvases signed by this name. There, I found some precious documents, not only about the work Carrière took on to live but about how his talent could adapt, about the various aptitudes that would allow him to fulfill the task at hand.

That’s all I had the energy for this week, but bit by bit, the bird builds its nest. Thanks for reading.

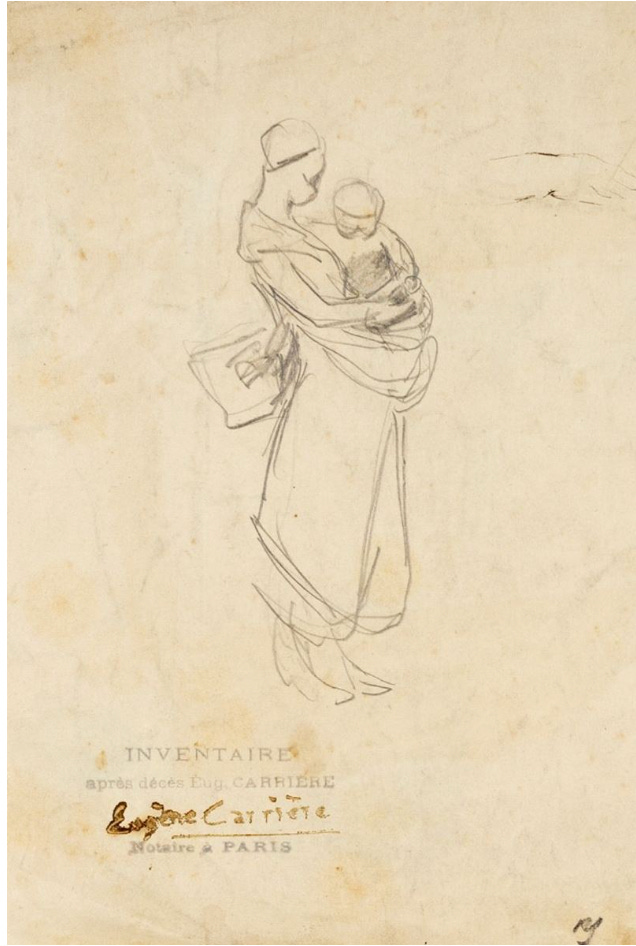

this section ended up being a bit challenging, but I gotta nail this line: he countered the weight of imprisonment with a courage that was serene, but faced might be the best option. There’s something to that, his quiet resistance, like he’s not going to get crushed by it, he’s meeting the reality of it, with a calm kind of courage. And, hey, the war ends in 1871, he’s gotta go back to his hard life in Paris — gotta be a painter. In 1871, he starts learning lithography. And I found this little preparatory drawing on an auction site. Shush.

Thanks for reading!