Um, Oxford drank out of an enslaved woman's skull, apparently.

Well, this one needs to be unpacked, a little bit, as a shocking reminder of how real and evil, even, colonialism was.

Wow, I flew here fast: I just covered the news reported by The Guardian. A professor and curator of archaeology at Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum was invited by the administration to investigate the origins of a chalice made from a human skull. And, well, Professor Dan Hicks wrote a book about it, and it’s coming out. It most likely belonged to an enslaved woman who lived 225 years ago in the Caribbean.

They drank from this cup ritualistically in the senior common room, bringing religious connotations to mind. Wine. The skull cup has been locked away since the practice terminated about ten years ago. Never to be seen again.

He believes a former British Royal Navy officer acquired this object from the Caribbean. It was put up for auction at Sotheby’s on a formal stand, made of wood, and it even bore a silver inscription commemorating the coronation of Queen Victoria. They served chocolates in it, once wine began to leak, like blood.

I swear to you, since people out there believe that I am psychic, even an X-Men, I finished it, posted it, and it totally disappeared. That has never happened in the year I worked for this company. Just vanished. I wrote the article off-site, so I just made it better, tried to, but it — boom. Gone. The entire doc. Vanished.

Hicks spoke about it in The Guardian with more authority than I have about erasure in British colonialism, in that, the skull’s ownership was well-documented, but any record of the woman’s didn’t exist. The cup was, then, for sale, and then passed down. It reflects the sick nature of attaching power and identity to degrading a human being. Even holding themselves up high about it. His book is called Every Monument Will Fall.

Speaking of, I examined the statue outside the Natural History Museum in New York City with President Roosevelt on a horse flanked by a Native American and an African. Inside, I read the public display of text correcting the racist depictions of Native Americans. They showcased their error. That felt appropriate to me. I wondered what people thought about Oxford stashing it away, never to be seen again. Hicks said it was ethical what they did.

It sparked so many questions about its acquisition as an object. It traveled through the hands of colonialists, regardless, beginning with a member of the Navy. A fascist supporter donated it to the museum, in the end. His grandfather founded it. But they honored the object, somehow, at Oxford, which raises questions as to even how the ritual began. It became a monument. One of the owners put his name on it, so it was stamped with political power and personal ownership. Did Sotheby’s go: this is a chalice made with skull?

Anyway, I remembered the year Rosa Parks' house came to Naples, Italy, for Christmas. She stayed for a while, as the season doesn’t really end. The exhibit was called Almost Home.

A construction company was going to destroy Rosa Parks’ house. And where were the emergency archaeologists then? Rushing to the scene? They tend to recover what they can because they can’t stop projects, or they cover it in a geotextile and bury it, again, so that’s what they do. There’s a project in Britain where the company will integrate the ruins into their design. In this case, you’d think, you can’t destroy Rosa Parks’ house.

An artist saved it, took it to Berlin, and it went on tour. In Naples, they famously revolt, so Rosa Parks did, you see, and it was how she did it. Major respect for Rosa Parks. Christmas in Naples is about immortality, and she is. This is an immortal being. We’re ancient in our understanding of things.

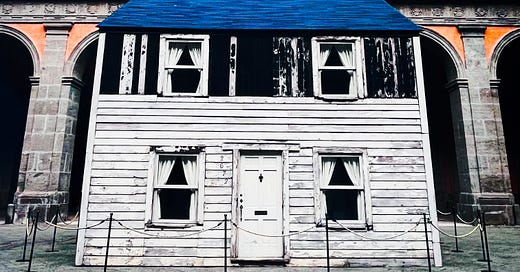

They placed her home in the center of a courtyard in the sumptuous Bourbon Palace, an example of baroque magnificence built in the 17th century. It became the seat of the Spanish Bourbons, where Ferdinand (played by Javier Bardem) struggled with this aspect of the Neapolitan character. Famously, a smuggling revolutionary (played by Joaquin Phoenix) spoke out against him. He even sent in mercenaries to kill him, and the Neapolitans killed them instead, and then, they charged the palace…Giggino, my cousin, was there, as he’s been present since the dawn of Neapolitan history, I’m pretty sure.

The photograph speaks for itself: her house in a splendid courtyard, and I can’t detach the associations with power, colonialism, and just the legacy of that history.

One could speak from various angles — she’s in royal circumstances as American royalty, and then, you cock your head at that, like, hmmmm, not so sure, about that angle. She’s one of the most important figures in civil rights, but how do you engage with the element of hierarchy and power that is omnipresent, even? It’s governance. But they gave the house a grand home.

I turned around, and there was a giant Christmas tree through the arch on Place Plebiscito, which is where many revolts have happened. It was significant in the Four Days of Naples when they kicked the Nazis out, as a city, led by GIGGINO and Joaquin Phoenix— so Naples has a rich history of foreign invasion, occupation, since the time of the siren from Odysseus.

In World War II, Black American soldiers were stationed here, apparently. I found a picture of a regiment of Black soldiers, mostly, in the Temple of Neptune. A racist song was written around this time, as an academic put it: “Tammurriata Nera as a Perverse Mechanism of US and Italian Colonialism.” To bring it back to the subject. The Americans rolled in once the Neapolitans kicked out the Nazis.

A boy was born to “an American soldier,” my cousin put it. He didn’t reference his race. I had asked him about it because I couldn’t penetrate the song, I’m not really from here. It has a catchy melody with “nera” in it: if you’d like to listen to it, I linked it. I tensed up, and Hick’s book made me think about the inclusivity in racist tactics, just how someone is included, where they say, it’s not racist, even.

Here’s a stanza:

Housewives gossip about this affair,

things like this aren’t rare, you can see thousands of them.

Sometimes just a look is enough

and a woman remains struck by the blow.

I don’t know if you read Christopher Moore’s book: Fighting for America: Black Soldiers—the Unsung Heroes of World War II. I didn’t finish it, but I started it a while back, and given how people were treated, I was taken aback by my cousin’s description. “It was an American soldier’s baby.” Thousands of them?

“The unsung heroes.”

Maybe Naples was populated with many American soldiers.

And Barbara Streisand came on—right after the racist song, “I am a Woman in Love,” the song Angelita taught me on my way to her house on Miracle Mile…

She’s dancing regardless of whether a catastrophe stands at her gates, regardless of whether her jungle home as an Amazon princess is at risk of being destroyed by evil white American contractors, and regardless of whether people mistake her for “Mexican,” just remembering The Forbidden Dance as a movie. And she, the actress, was actually Mexican, not Brazilian. I watched it again. She would fast forward to the sexy parts — no shame. I laughed at her, from beginning to end.

I thought about the structural component of racism, Rosa Parks’ house in the context of a palace. The idea was to honor her and respect her, I think. I suppose they sought to give her a crown, give her shelter. A queen. Even sanctioned by God, as that’s how power, back then, was generally assigned. But the history of racism within these structures is still present, regardless of intention.

But it’s a monument, I believe, to her power and her glory, a woman to cover in gold, which is strange as an idea, to me, given what she stood up against. I mean, a woman wearing a suit to come across as powerful, let’s say, rather than a dress. Either one works. But she’s a statuesque figure, even a pillar. Her little house made a real impact against a real giant. All that history: architecture. All present. Still in conversation. A striking image.